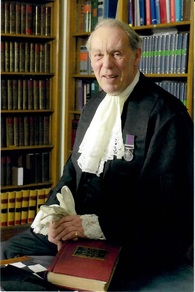

Robert Turner (47-49) Visiting Professor to the Faculty of Law at The University of Cambridge writes:

I am in the course of writing an account for my grandchildren of my life and I enclose a few pages dealing with the opening of the Choir School after the War as I appreciate that there are now very few of us from this glory days!

Although we are celebrating the 100th anniversary of the opening of the School, it will be 70 years in couple of years time since the Choir School was reopened after the War and it might be of interest then in 2017 for an account however personal to be available. I hope to be there especially as I have to give a lecture at the Royal University in Copenhagen on the Origins of English Kingship which I don't want to miss.

Some years ago I wrote an account of the Shields in the aisles. I have finished it and one day when the pennies are there I might get it printed but as it runs to 70 pages with coloured pictures of the 40 shield, the expense may be too much.

I read with interest the article on the Henry V helm and sword (in the Magazine). In 1948, McKie and Mr Tanner took three of us to the triforium and there under some straw was the sword, hidden there throughout the War. I remember holding it aloft and it was so well balanced that a 12 year old could easily weld it. I am still enjoying life. I live a very pleasant new life as a professor of law at Cambridge where Clare College look after me. The senior organ scholar holds the William McKie

scholarship.

(from Robert's as yet unpublished book)

Chapter 12

The final Choir School

My parents never gave up in their quest to get me to a choir school for which I am grateful. One day I was taken to Westminster Abbey to be auditioned by Dr William McKie, the Master of the Choristers and Organist at the Abbey. The audition was to join the Abbey's London Choir. At the start of the War the Abbey Choir moved out to Charterhouse in much the same way as the St Paul's Choir had moved to Truro but in the case of the Abbey it was not a success and the choir was disbanded for the duration of the War. In its place the second organist Dr Ossi Peasgood who was deputising for Dr Mckie who was in the RAF, formed without seeking Dr Mckie's advice or permission a choir of boys drawn from the suburbs of London. They went to the Abbey on a Thursday evening to practise and then sung two services on Sunday's. Peasgood was an easy going choir master but a robust organist in the traditionalist sense. He played the magnificent Abbey organ with all the loudest stops in action. Such was the volume that the Clerk of Works feared for the fabric of the building. On his discharge from the RAF, Dr Mckie had the task of rebuilding the choir. He was a perfectionist and not impressed by the somewhat lax standards that he found on arriving at the Abbey.

Dr McKie, an Australian, had been the City organist at Melbourne followed by appointments at Clare College Cambridge where there is still a organ scholarship named after him, Radley, and at Clifton followed by a spell at Magdalen College Oxford before being called up into the RAF. He was appointed the Abbey's organist in 1940 but had no contact with the Abbey, which had by then no choir, until 1945. In his absence Dr Ozzie Peasgood, a brilliant organist though a hopeless choir master had started the London choir recruited from boys living in the London area who were able to come to the Abbey on Thursday evenings for rehearsals and then sing Matins and Evensong on Sunday's. It was relatively successful though I suspect the standard was not as high as might be expected of the normal choir or did it meet Mckie's own high standards.

It was into this choir that I gained a place. I remember my very first evening service on a wet dark Sunday. It was a special service to commemorate the founding of the Army charity Toc H by the Revd Tubby Clayton. My father took me up on the tube to attend the choir practice and to attend the service. I wore just the red cassock and was not required to sing. But there was a curious twist to this service as my father when acting as Town Captain of a small town in Flanders had been responsible for finding the house which the Revd Clayton was seeking to house his mission to provide a quiet rest hostel for soldiers out of the line during the First World War. The house is still there in France.

The routine required of us boys was to find our own way to the Abbey on Thursday nights, in my case that meant catching a District Line train from Ealing Broadway to St James and after an hour's practice to find our way home. This was in 1945 or 1946. On Sunday's the routine was to get ourselves to the Abbey by about nine o'clock for the first practice of he day, sing Matins and on occasions Sung Eucharist though this service was not in those days the main Church of England Service as it is today, break for lunch in a local pub and return for the second practice before Evensong. I suppose there may have been the

occasional evening service but I do not recall this. We also had to attend any Special services.

The pub lunches were the high light of the day as we had as much as we could eat of a selection of cold meats and the delight of very strong piccalilli. Afterward we were let loose only being required to get back to the Song School in good time for the afternoon practice.

We usually had just an hour of free time which we put to good use with our favourite pastime of going to the ruins of the church in St John's Square and climbing onto the parapet and traversing round the church without falling off - had we done so it would have been serious.

The London choir was a mixed bag. Ossi Peasegood was a gentle soul who just wanted the choir to sing a reasonably good service and not be too strict about the quality of the performance. In a sense this was a reasonable compromise. The boys came from all parts of London at some considerable inconvenience to themselves. The men Lay Vicars, though professionals played ducks and drakes with the system by attending both the Abbey and St Paul's on the same afternoon or morning and thus doubling their earnings.

They had stand ins to cover them if they could not make a service or might be seen to be leaving the quire before the sermon in order to get to the start of the service at St Paul's. They seldom arrived for the practice before any service more than five minutes to the hour on the basis that they knew all the music backwards.

In a sense the boys were also professionals as we were paid five shillings a quarter, half a crown for attending a special service and five shillings for any service that might be broadcast. The fee for singing the services over three months worked out at a penny a service! I can't be sure if we were paid our tube fares but I suspect we were. I put all my money into a Post Office savings account and shortly before the Choir School opened and I became a boarder, I withdrew all my savings and bought a camera. My parents were horrified but as I pointed out, I had earned my monies - the hard way.

The Choir School was a large five or six storey brick building on the west side of Dean's Yard. It had been requisitioned by the War Office and the Dean and Chapter had been unsuccessful in their efforts to have it returned. On day we noticed that the famous Field Marshall Montgomery was sitting at the back of the Quire Stalls. We told Dr Mckie who spoke to him after the service and the result was an invitation to tea at Montgomery's flat near the Abbey.

He asked Mckie when he might expect to hear the proper choir back in the Abbey. Mckie pointedly replied ’when your lot give us back the Choir School". The building was returned within two weeks and a generous sum was paid to restore it to its pre war state - some achievement at a time when building supplies were virtually non existent.

The Abbey advertised for boys to join the choir as boarders but decided to initially keep half the London Choir to ensure continuity. I was auditioned by Dr McKie who wanted to recruit as borders the best of the London Choir and to my astonishment I succeeded in getting a place. Some years before my father had promised me a pair of Ivory handled hair brushes if I won a place at any of the choirs which I had tried to join. On the morning of being told of my success at the Abbey my father woke me by handing me the pair of hair brushes. Without saying anything, I knew exactly what he meant. I needed nothing more to tell me that I was off to become a member of the full Abbey Choir. I still have one of the brushes and use it daily.

Chapter 13

Life at the Abbey

Starting a school from scratch must have been a daunting task. The school itself had been refurnished with some new items but mostly with furniture saved by the Abbey's Clerk of Works from the pre-War school which included the iron bedsteads which were very uncomfortable. The next door house which should have been the home of the headmaster and his wife was still occupied. They had to make do with a flat on the fifth floor immediately beneath the top floor covered playground around which we thundered on roller skates which in those days had metal wheels.

Our meals were cooked in a very small kitchen on the first floor adjacent to the hall which doubled as a class room and eating hall. In the first basement there was a gym and our personal lockers. In a very dark lower basement some of us established a photographic dark room. Rumour had it that there was yet another basement below this one but we never managed to get the door open despite our efforts to do so.

Out side at the back was a small yard surrounded by the music practice rooms as each of us had to try to learn at least one musical instrument, mainly the piano. I tried to master my over sized violin but without success. We had a musical theory lesson once a week but I was hopelessly out of my depth. I hadn't a clue what they were all talking about - indeed it was not until I started recently to learn to play the piano under Emma Bonner Morgan in Stowmarket that I was able to ask about many of the mysteries in music which J have met in those days.

The staff was equally remarkable. The Headmaster was Edward Thompson, who had been a housemaster at Sherborne. He had no academic qualifications whatsoever but was regarded by all who met him as one of the most gifted of schoolmasters. Unbeknown to us he had once been regarded as the successor to Baden-Powell as Chief Scout. He had a very loving wife. His life had been devoted as was her's, to the Scout Movement and he was known to all by his Scouting name, Mingan, by which he was addressed by the youngest boy to the Dean himself. No question of him being called "Sir" by us or "Mr Thompson" by others.

He and his wife were saints. Each evening we were allowed to use the covered Tarmac roof play ground to roller skate on. The skates had metal wheels in those days. The noise in the Headmaster's flat beneath was worse than any noise created by the 'planes at Heathrow. His response to any who visited him during the hour in the evening when this occurred was that the boys needed the exercise as they worked so very hard. Indeed we never had home work in the traditional fashion as he insisted that we needed our own free time.

The second master was Edward Pine who had been a master at a mysterious choir prep school in Worcestershire called St Michael's, a school created in the 19th century by a very rich man who wanted a choir to sing the traditional services of the Church in a very large monastic abbey that he had founded and housing many monks. It had a remarkable choral tradition but slowly faded away when its founder died.

Edward Pine was an inspired history teacher to whom lowe my enduring love of the subject. Although I doubt if it still exists at the choir school, he made the boys in the top history form read the newspapers each day and to select an item which we thought might be of lasting interest. Before it was pasted in a large scrap book, we had to justify to him why we thought it was of historical significance. This was at a time of the start of the Cold War in Europe, the fall of many European countries to Communism, the start of. the Welfare State and the like. The book had it been preserved would have been of listing interest.

But the outstanding man at the Abbey was Dr William McKie. When he came to the Abbey in 1945 he had only the London Choir with which to work. The opening of the Choir School gave him the opportunity to reestablish the musical traditions of the Abbey but in his own very individual form. Though it might seem to be of little significance nowadays, one of the first steps that he took was to purchase fifty copies of a new American edition of the Messiah. The Lay Vicars and others were horrified not to be using the traditional Novello score. He also stopped their habit of singing two services morning and afternoon at the Abbey and St Paul's.

He was a perfectionist and his loss of temper was known to all. Many a hymn book was caught by a member of the choir at whom it had been thrown by William when he thought the boy had sung a wrong note. Once he threw a large wooden music stand at the Head Chorister who deftly caught it and replaced it without saying a word. On one occasion he stormed out to Abbey and retired to his flat in Victoria for three days because he felt the choir had performed badly and it took the Dean himself to visit him and to persuade him to return. The boys in the choir took all this in their stride and the Head Chorister ran the choir practices in Mckie's absence.

One of us always had to go to the organ loft to turn over the pages of the scores during the service as the Abbey had a four manual organ and hundreds of stops which meant that he organist had much to do apart from turning over the pages. It was a very nerve racking task as you needed to know exactly where he was in the score and turn the page just before the last bar on the page. Get your timing wrong and William would let you know! It was also the unpleasant task of the organ loft boy to go to the West Cloister door when Dr McKie was dissatisfied with the choir's performance, and await the choir as it processed out and to inform the Head Chorister. "Dr McKie wishes the choir to stay behind in the Song School". This meant that we were to receive one of his notorious outbursts of displeasure.

To be continued